FRIEZE MASTERS

15–19 October, 2025

The Regent’s Park

London, UK

15 October, 2025: VIP Preview

16 October, 2025: VIP and Members only Preview

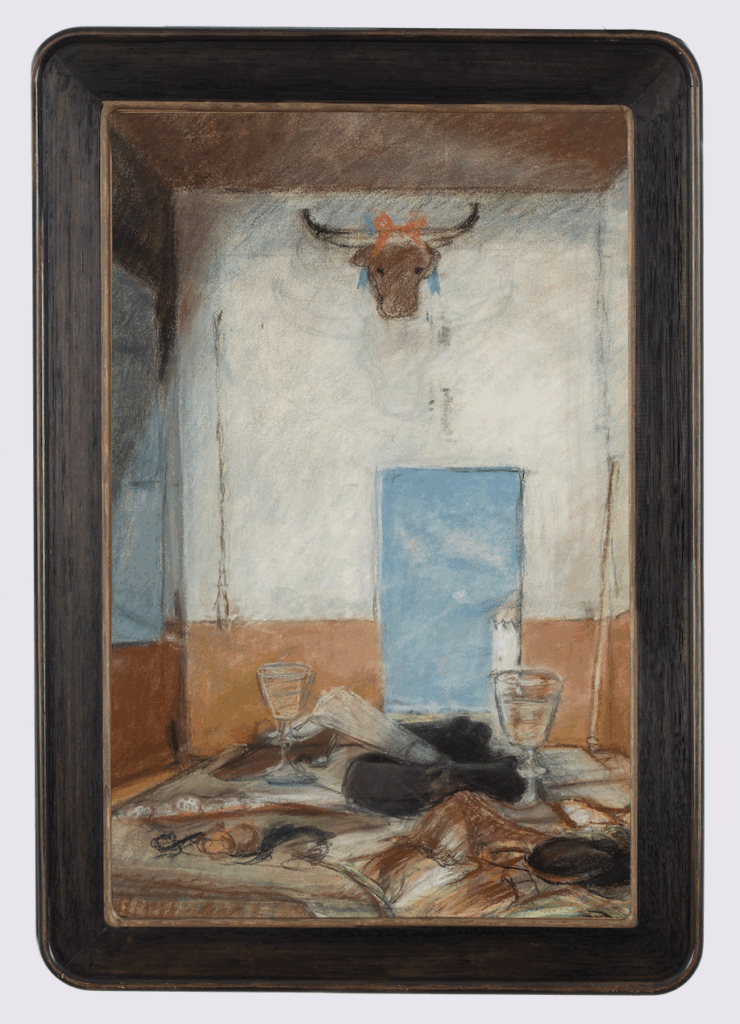

PIERRE ROY Retrospective

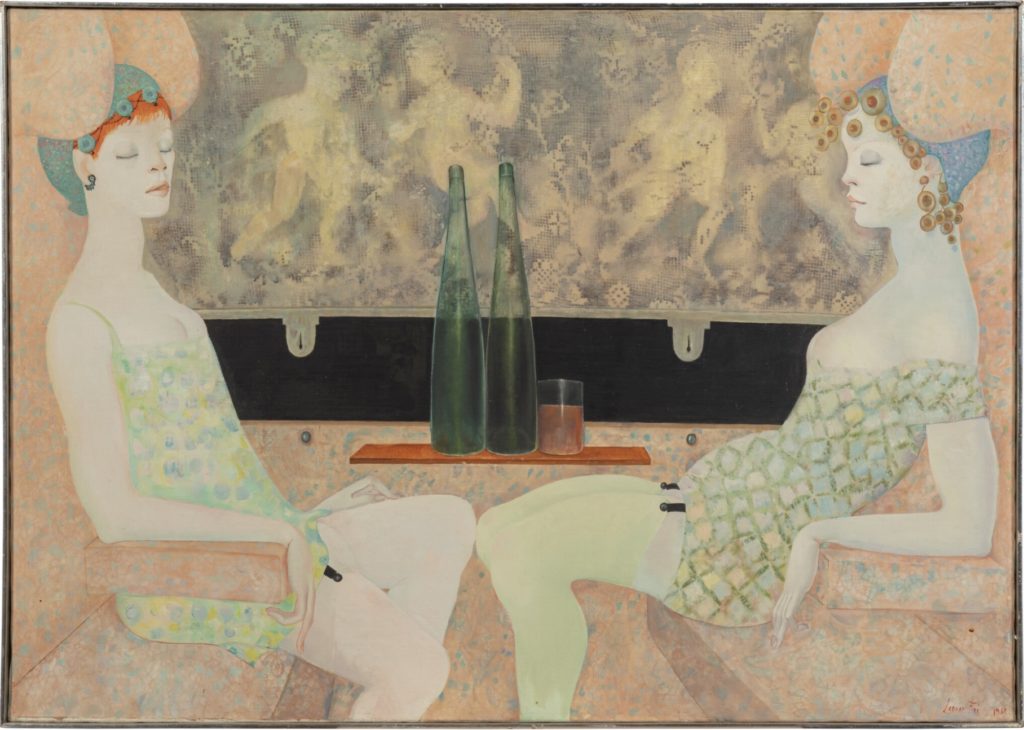

Major works by LEONOR FINI

Booth F14

For its second participation in Frieze Masters London, Galerie Minsky is pleased to continue the path opened by its long-standing work around Leonor Fini, turning this time to another artist whose oeuvre evolved on the margins of official Surrealism as theorized by André Breton. Mounted in collaboration with the artist’s heir, the presentation explores Pierre Roy’s (1880–1950) unique position within the trajectory of modern art and in the history of its reception. The exhibition aims to introduce the public to the artist’s works dated 1910-1948 while juxtaposing them with a few significant pieces by Leonor Fini.

After a recent rediscovery of Roy at the Centre Pompidou for the Surrealist exhibition, the artist was also presented at the Musée Marmottan Monet in a landmark show on the history of trompe-l’oeil. His paintings are owned by the MoMA (New-York), Centre Pompidou, Tate (London), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musée d’Arts de Nantes (selection).

Included in the very first Surrealist exhibition at Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925, the Nantes-born painter had already been singled out by Guillaume Apollinaire as early as 1913, when one of his paintings was shown at the Salon des Indépendants.

Yet unlike many of his peers, he slowly and amicably withdrew from the group of revolutionary young artists, refining instead a highly personal language of painting that reflected his deeply individual temperament. As he put it: “I do not like to belong to any group whatsoever, but I remain on very good terms with Aragon and Éluard.” His words resonate with those of Leonor Fini, who, despite her friendships within the Surrealist circle, rejected Breton’s dogmatism and refused the “Surrealist” label altogether: “I have never seen the point of belonging to a group… I have never been interested in ideologies, and in the 1930s I refused the label ‘Surrealist.’ I have never been Surrealist; I prefer to follow my own path”.

Roy’s work remains profoundly connected to certain Surrealist principles—unexpected juxtapositions of objects, or distortions of scale, as in Moules sur la plage (1945)—yet he applied such ideas instinctively, before they were codified in manifestos, and without the impulse to systematize them. Rather than pursuing chance procedures such as collage, frottage, or automatism, he was drawn to the slow, precise depiction of real and cherished objects. From around 1910, still life became central to his practice, gradually overtaking the sensitive portraits of close family members that carried such intimate weight for him (his beloved Adrienne Ridou would die young in 1919). Removed from their natural environment and placed within the still life setting, the objects painted by Roy reveal their ‘thingness’ — their essential objecthood — giving rise to a gentle sense of strangeness, one that is not sought for its own sake (Leo T. Hurwitz, “Mice and Things: Notes on Pierre Roy and Walt Disney”, Creative art, May 1931).

The artist’s role in the American reception of Surrealism was decisive. In 1930, the Brummer Gallery in New York devoted a major solo exhibition to the artist, followed by his participation in The Newer Super-Realism (Hartford), organized by A. Everett Austin and Julien Levy. Museums such as MoMA and the Wadsworth Atheneum soon acquired his works, and contemporary critics noted that alongside Miró, Roy was one of the most discussed artists in New York in that period of time. His meticulous craftsmanship, which could have been criticized by Breton or Robert Desnos in France as too classical, paradoxically became an asset across the Atlantic, where it allowed him to embody the very essence of Surrealism while avoiding the pitfalls of fashion or dogma. The Wildenstein & Co gallery, traditionally associated with works of high prestige and particularly known in the 1930s for its specialization in 18th-century French paintings, drawings, and sculptures, dedicated a solo exhibition to the artist in London in June 1934.

Pierre Roy’s creative process echoes, up to a certain point, that of his friend Giorgio De Chirico and what was called ‘metaphysical painting,’ whose metaphysical character resides precisely in mimesis; “it is this same quiet and absurd beauty of matter that seems metaphysical to me, and the objects which, thanks to the clarity of color and the precision of their volumes, are placed at the antipodes of all confusion and obscurity, seem more metaphysical to me than other objects” (De Chirico, 1919).

Pierre Roy’s creative process echoes, up to a certain point, that of his friend Giorgio De Chirico and what was called ‘metaphysical painting,’ whose metaphysical character resides precisely in mimesis; “it is this same quiet and absurd beauty of matter that seems metaphysical to me, and the objects which, thanks to the clarity of color and the precision of their volumes, are placed at the antipodes of all confusion and obscurity, seem more metaphysical to me than other objects” (De Chirico, 1919).

More recently, in the 1980s, Whitney Chadwick’s seminal book Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement shed new light on Pierre Roy, offering an opportunity to reassess not only the crucial role of women within this modern artistic climate but also the contributions of other marginalized figures. Several of the works exhibited illustrate both Roy’s technique and his mental process in a very obvious way. Le Lion dans l’escalier, 1928—a precursor to Danger dans l’escalier (MoMA)—was born of what he described as “the feeling of fear that takes hold of me when I visit a stranger in a house where I know no one”. As it is often the case in his work, Roy reached an adequate pictorial expression of an inner state only through a series of patient, successive attempts. Several “objective” landscape studies, such as those created in Hawaii in the late 1930s, led him to forge a deeper connection between his later still lifes and the skies, clouds, and trees he witnessed, extending them into new atmospheric registers. As early as 1915–1920, in works such as Portrait of Adrienne Ridou and Sieste devant le château, hats, distant castles, and enfilade interiors were already present, forming the motifs that would define his artistic vision and captivate audiences in his most celebrated paintings. Perhaps more touching than all the other objects is Pierre Roy’s recurring ribbon, as seen for example in the 1928 still life—more meaningful and concrete than that the knot that troubles the anxious and tightens the chest (Jean Cocteau, preface to Pierre Roy, exhibition March 4th to April 15th 1933, Brummer Gallery, NY). The pastel Hommage à Goya, 1947 refers to a commission initiated by the Museum of Castres and to correspondence between Pierre Roy and Gaston Poulain, which more than anything else reflects Roy’s exacting standards—the necessity to access the objects, a commitment to historical accuracy, and the freedom to study the materials closely. This same rigor is evident in the magazine covers Pierre Roy created, which earned him the title of Vogue’s go-to cover artist during the 1930s and 40s. Roy was the first to grasp the vast potential that advertising held for art — the first to open a door through which Magritte and Dalí would later rush in, decades ahead of anyone else.